QR Code Error Correction for Programmers

QR Code Error Correction for Programmers

Error correction is often obscured behind high-level abstract mathematics, and for good reason. It’s a complicated subject, and there are many approaches for different types of situations. I’m not aiming to cover all of error correction in depth, just the basics necessary for QR code decoders.

QR codes have various mechanics for error correction, the biggest of which is Reed-Solomon error correcting codes. These are specially created numbers that, even if we are missing some of them, or some of them are wrong, we can detect and correct the mistakes (as long as there aren’t too many).

In this first part, we will go over the math fundamentals. If you’re already well versed in finite field arithmetic, feel free to skip to the next part where we focus on Reed-Solomon. This tutorial is aimed towards programmers at a relatively basic math level, so I’m assuming you have a decent grasp on algebra, and not much else. If you don’t, there are plenty of great resources online, like Khan Academy.

Overview of Reed-Solomon

Reed-Solomon error correction is a systematic, maximum distance separable code using symbols represented as polynomials with finite field coefficients. Unless you understand coding theory, that sentence probably means nothing to you.

Let’s start with this idea: When we represent data as equations, we can solve for unknowns.

Say you have two numbers and and you’d like some way to correct for errors.

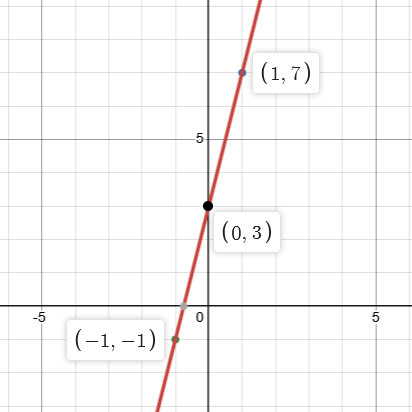

You can setup an equation like . Let’s pick three points on that line:

Now, if something happens and you only have two of three points

We can still work out what the original equation is:

We know the equation is in the form:

So we can substitute the values and solve the system of equations:

Using

We substitute with in the other equation:

Now it’s a matter of substituting with

So we have worked out both and

Just like that, we have a rudimentary form of error correction.

If we have two numbers, we can make an equation out of it. Then, we calculate some points on the equation. Given three points, we can work out what those two numbers were, even if one of the points is unknown.

This is called erasure correction because we know where the error happened.

But what if we don’t know the position?

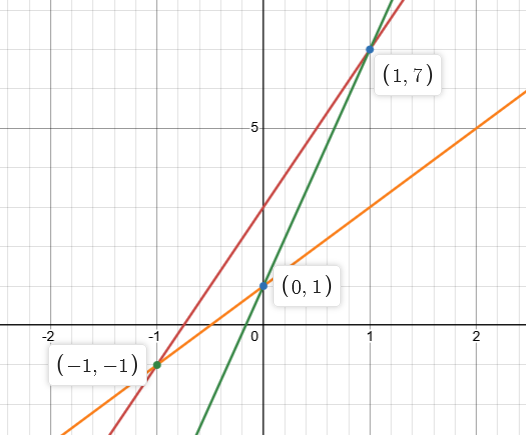

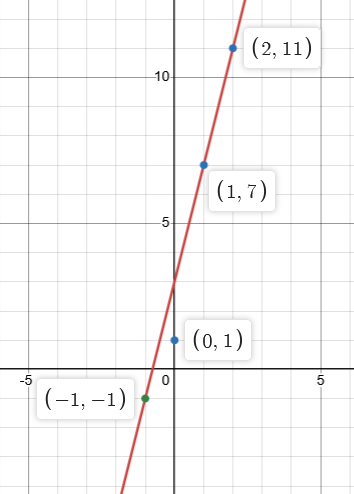

Let’s say you have these three points:

As you can see, there are three possible lines we can form from these points. With our current setup, we can detect one error, but we cannot correct it if we do not know the position.

If we have four points, the error becomes obvious:

It looks like we need two extra points to correct each error, but only one extra to correct an erasure. If we only have one extra point, we can still detect an error even if we can’t correct it.

Reed-Solomon uses a similar concept, but with a more nuanced approach - instead of using regular numbers, we use a Galois Field. This is so that data can be represented more efficiently. In a real scenario, QR codes can store thousands of bytes. Trying to form systems of equations with thousands of coefficients would get out of hand very quickly. Galois Fields are a unique number system that solves this issue, as well as enable efficient ways to solve equations.

Galois Fields

Galois Fields, or Finite Fields as the more technical name, are a field of numbers with a limited set of numbers. They are referred to using where is some whole number.

You might be familiar with several fields of numbers:

- the field of integers:

- the field of real numbers:

- perhaps even the field of complex numbers:

These are all infinite fields. That means whenever you add two positive numbers together, you will always get a bigger number.

and so on, infinitely.

Galois Fields are finite fields - the possible numbers you can use is limited.

For example, in , there are only three numbers: , , and . All operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division) will result in one of those three numbers.

e.g.:

Similarly,

This looks like regular arithmetic except you modulo the result by the Galois Field number. In QR codes, we will be using two particular Galois Fields: and

Galois Field 2

has some unique properties that are convenient for implementing in software. In , there are only two numbers: and . This means we can represent a number as a single bit.

Operations in have convenient overlaps with binary. Take addition, for example:

If you know your truth tables, this should remind you of exclusive or, or XOR.

But what about subtraction?

Both addition and subtraction are the same in .

Multiplication is different however:

But is just as easily represented with AND.

Division is even more strange:

We can only divide by 1, since we cannot divide by 0. And so, division has no effect in

But QR code Reed-Solomon does not use , instead it uses .

Galois Field 256

Simple Galois Fields can only be prime numbers, because otherwise you end up with broken math rules. For example, if that must mean or (or both).

This is fine in e.g. , since

so the rule holds up.

But if you tried to make a then you end up with

which would mean that either or , which can’t be possible.

So then how is possible? There is another type of Galois Field, which is in the form where is a prime number. Instead of using simple modulo arithmetic, numbers are represented as polynomials of degree with coefficients in

, meaning that is the same as . We can represent numbers as polynomials of degree with coefficients in .

This is useful because when we represent numbers as an 8-bit unsigned integers, each bit in the number corresponds to a term in the polynomial representation.

= 0b10011001

= 0x99

= 153Conveniently, addition and subtraction in can be implemented in the same way was in

Say we want to . In binary, this looks like:

153 = 0b10011001

+ 212 = 0b11010100In polynomial representation, this looks like:

The actual operation we perform is

0b10011001

^ 0b11010100

----------

= 0b01001101Which equals

XOR is performed bit-wise, so with one instruction we are XORing ( -adding) each term in our polynomial representation.

Multiplication and division works using polynomial math. However, software implementations use a trick with logarithms to make computation quicker and easier.

Log rules

You might be familiar with rules for logarithms , but let’s quickly brush up on them.

The log function does the opposite of the b^i power operation for a given base b:

e.g.

Often the base isn’t written, especially if the base can be inferred from the context.

There are a handful of log rules, but the two most useful for us are:

There is also the antilog, which performs the opposite of a log:

The log function is already doing the opposite of a power, so the antilog is another way of raising to a power. It’s just easier use antilogs so we don’t have to specify the base.

With these log rules, we can now define multiplication and division:

But this leaves us with a different problem. How do we get the log of a number?

Generator Element

All Galois Fields have a special number called the “generator number” or “generator element”. Every number in a Galois Field can be produced by raising the generator element to a power (apart from ). In math texts, the generator element is usually given the symbol (alpha).

The math explanation sounds a bit abstract, but it becomes easy to grasp once you see it in use.

In the generator element is , or in polynomial representation.

Things are getting a bit convoluted here, and there’s a lot of representations to keep track of. Let’s go through them one by one.

, we know this because the base of the antilog is , and . In polynomial representation, that’s equivalent to , which is . As an 8-bit binary number, it’s the first bit: 0b00000001.

In order to find the next power of , we need to multiply the previous element by . We know that , so this is equivalent to multiplying the previous number by .

If you pay close attention, you might notice that this is also equivalent to a Left Bit Shift << in binary, or multiplying by in the polynomial representation.

We keep multiplying the previous number by to get the next. But once we reach , we have another problem. The largest number in is , and . What happens we produce a result outside ?

Prime polynomial

The third and final Galois Field concept you need to understand is the prime polynomial. Just like a prime number, a prime polynomial cannot be reduced. There are actually many prime polynomials for any Galois Field (in there are 30).

In QR codes, the spec tells us to use the prime polynomial . It is often represented in code as 0x11D. The math behind prime polynomials is complex, and not strictly necessary to understand for implementing error correction, so we will gloss over it here.

For our purposes, the prime polynomial has the same purpose the Galois Field number - when we produce a number outside the field, in polynomial representation we use the remainder after dividing by the prime polynomial (the modulo operation).

Dividing polynomials sounds tricky, but it’s very similar to long division with regular numbers. We’re in luck though, because we technically don’t have to do it.

In our case, we have to find the remainder of:

which looks like

Without going into too much detail, notice that both polynomials have the same leading term: . This will always be the case in our scenario where we multiply the previous value by , and the result is . So all we have to do in order to get the remainder is to subtract the prime polynomial.

In binary:

00000001

___________

100011101 ) 100000000

^ 100011101

---------

00011101Remember that subtraction in and is equivalent to XOR in binary.

And now we know that in , . What a world we live in.

With that out of the way, we can continue with our antilog table.

Keep multiplying the previous entry by , and once you produce a number you subtract (XOR) the prime polynomial to get the remainder. After calculating each antilog from 0 to 255, we can calculate all the logs using some more log rules:

Put simply:

Recap & Conclusion

That was quite a lot of sub-problems we had to solve, so let’s take it from the top:

We learned that QR codes use Reed-Solomon error correction, which encodes data as an equation we can solve.

Then we learned about Galois Fields, which have a finite set of numbers, and use modulo arithmetic to keep the results of operations within the field. There are only two Galois Fields we are interested in:

, which only has the numbers or , much like a bit. Due to overlaps in the modulo arithmetic and bitwise operations, addition and subtraction can be performed with XOR.

is a special Galois Field in the form of . These Galois Fields cannot be represented with regular modulo arithmetic, and instead use polynomials of degree with coefficients in . Conveniently, due to overlaps in polynomial and binary representation, we can still perform addition and subtraction using XOR.

Multiplication and division in requires complicated polynomial math, but we can simplify it using logarithms instead.

Each Galois Field has a “generator element” which when raised to each power can produce every number in the field apart from 0.

We can calculate all the antilogs of the generator element by raising the generator element to all the powers from 0 to 255 (effectively, starting at 1 and multiplying the previous by , or using left bit shifts).

If we produce a number greater than , we have to modulo by the prime polynomial . In our case where we are producing the antilog table, we can simplify the modulo operation to a single subtraction (XOR) of the prime polynomial.

We can then calculate the logs from the antilog using

Finally, to multiply two numbers, we can use the equation , and to divide

For example:

NB: , because the powers of loops on modulo .

With that, we have covered the math fundamentals required for Reed-Solomon. You might need to go over it a few times before you grok it, feel free to come back if you’re confused. Otherwise carry on to Part 2 (TBC)